all text articles

Home > list > international

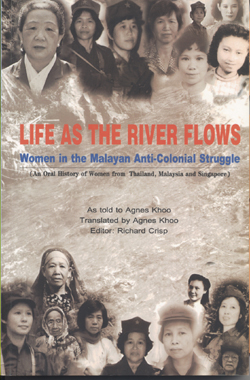

Life as the River Flows

A Historical Overview of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM)

Agnes Khoo(University of Menchester, UK)

This web-based and condensed version of the book, "Life as the River Flows" focuses mainly on the struggle for independence from British and Japanese colonialism between 1948 to 1989 in Malaysia and Singapore. The stories have been told from the unique perspective of a group of women ex-guerrillas of the Communist Party of Malaya(CPM), who live in four different ‘Peace Villages’ in Southern Thailand today. Many of them cannot return to their homeland because of their involvement with the Communist Party of Malaya. The CPM has not only been outlawed by the British and the Japanese colonial governments but also by the post-independent governments of Malaysia and Singapore even until today.

The approach for this series of write-ups will assume that most readers have little intimate knowledge about the history, geography, demography and the socio-cultural atmosphere of Malaysia (which consists of East Malaysia i.e. Sabah and Sarawak and West Malaysia) and Singapore.

Malaysia today has a population of more than twenty million and Singapore, about four million – comprising of mainly Malays, Chinese and Indians, but also a number of other nationalities and ethnic minorities. These are namely, the indigenous communities like the Ibans and Dayaks, descendents of early migrants from as far as the Arabic countries to as near as Indonesia, Eurasians who are of Portuguese or European descent. The last two to three decades of economic affluence in Malaysia and particularly in Singapore, also saw a rapid rise in the number of migrant workers from neighbouring Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand, Sri Lanka, Burma, Bangladesh, India, the Philippines, and increasingly, China nowadays.

Before 1963, Malaya, as then it was called, consisted of eleven states, which included the Peninsula of Malaya and Singapore. However since 1963, the former British territories in Borneo, i.e. Sabah and Sarawak were merged with Malaya to form the Federation of Malaysia. This was an arrangement the British colonialists made to forestall the possibility of Borneo territories falling into the hands of neighbouring Indonesia, which was then led by anti-colonialist and nationalist President Sukarno. He was eventually toppled by Suharto in a military coup with the support of the CIA and the US government. As a result, the people from Sabah and Sarawak were never democratically consulted in the way their independence should have been determined. Therefore, the left wing and progressive movements in Malaysia and Singapore the CPM being only a part of it, never recognised Malaysia as a legitimate country. They also saw the separation of Singapore from the Peninsula of Malaysia to form an independent state on its own, as a ‘historical mistake’ made by the overly ambitious Lee Kuan Yew, the then Prime Minister of Singapore. That is why the CPM continued to refer to Malaya, which includes Singapore, and not Malaysia.

During the British colonial period, most of the Malayslived in the countryside as small farmers and peasants. Traditionally, Malay society tends to be feudalistic in structure and practice, based on a social hierarchy of highly differentiated power relationships with the King/Sultan at the top. Each state in Malaya or Malaysia as it is today, would have its own Sultan. When the British colonised Malaya, they kept the Sultans only as figureheads and deprived them of any real power to rule. To maintain overall control over MaIaya, the British tended to use ‘divide-and-rule’ by playing one Sultan against the other or supporting one brother within a Sultanate over the other in their power struggle.

The Malay society was also traditionally an agrarian society, mainly of landlords and peasants, including many tenant farmers. From the 19th Century onwards, the British brought many Chinese peasants from Mainland China who were keen to escape poverty into Malaya as migrant workers. As a result, the Chinese formed the largest single group of migrant labour in Malaya all throughout the 1950s. At around the same time, the British also brought many poor Indian peasants from the Southern Indian State of Tamil Nadu to Malaya, mainly as indentured labour to work in the British-owned rubber plantations. India was still a colony of the British Empire then.

Hence with these early ‘division of labour’, the three major racial groups in Malaya were kept by and large segregated from one another by the British colonial government’s deliberate divide-and-rule polices. Even though the CPM was able to recruit members from all the three different communities, it was however most successful in attracting and retaining Chinese members. Among many different reasons, the history of its formation probably played a decisive role.

The CPM was founded in April 1930 in a small village near Kuala Pilah in the State of Negri Sembilan (part of the Peninsula Malaysia). Before its establishment, it existed only as a branch of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and was known as the Nanyang Communist Party (i.e. Southseas Communist Party in Mandarin). It consisted almost entirely of Chinese migrant workers from Mainland China, particularly those who were being persecuted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuo Min-Tang or KMT which ruled Taiwan as a single party until 1994) led then by Marshall Chiang Kai-Shek; who later became the first President of Taiwan.

On 30th April 1930, the Shanghai-based Far East Bureau of the Comintern (Communist International) helped organize the first Party Congress of the CPM with Ho Chi Minh attending it as its representative. Ho was then working as a representative of the Comintern. In its early years, the CPM operated as an underground organization. It experienced enormous hardships and was severely hunted down by the British colonial government. The British ferociously arrested, detained and executed party members as well as people who were suspected to be members. Even sympathizers or people who were only remotely associated with such persons were not spared the prison or gallows. Those CPM members who were not sentenced to death were quickly deported to China, even though some of them were actually born in Malaya or have already lived most of their life in Malaya.

However, the CPM were still able to organize workers in the plantations (mainly rubber, oil palm), as well as in tin and coal mines. Workers in the transportation sector of the economy were also recruited and became active members. These establishments were owned mostly by the British and their collaborators. Furthermore, high school students from Chinese schools where the medium of teaching is Mandarin or a specific Chinese dialect also formed a potential pool of recruits for the CPM-led or CPM-influenced student movement and mass organizations. This was in stark contrast to the English-medium schools where the students tended to be much more elitist and pro-British.

When Japan invaded Southeast Asia, the British did not defend Malaya for very longbefore they surrendered both the Peninsula Malaysia and Singapore to the Japanese army. It was an unconditional surrender within 24 hours of Japanese invasion in some parts of Peninsula and in Singapore, despite the confidence of the colonial government of its prowess in its navy and weaponry. The Japanese nevertheless was able to take the colonial army by surprise by literally cycling southwards into Malaya through the border with Thailand in a swift capture, destroy and occupation mission, while the British cannons stood aiming for its enemy at the other end of the Peninsula, towards the Pacific seas.

In fact, the only organized defence then came only from the CPM. And it could only rely on very rudimentary weapons and soldiers with very little training. Therefore, the party had no choice but to enter into a strategic cooperation with the British colonial authorities, so as to gain proper military training and obtain better firearms to defend themselves and the Malayans against Japan. In return, the British released jailed CPM members to form the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), which could then carry out guerrillas operations inside the country just behind the enemy’s line. This tactical coming together between the two enemies lasted from 1941 to 1945 until the end of World War II.

In fact, the MPAJA was even honoured by the Queen of England in 1946 for its contribution to the defeat of Japan with several of its top leaders invited to London to receive their medals. Chin Peng, the Secretary General of the CPM was among one of those honoured. The quote at the beginning of this chapter by Peter Waterman refers precisely to this event. Ironically, soon after this, Chin Peng was named by the British Empire as Enemy Number One and Malaya’s top terrorist on the British most wanted list with a hefty bounty for his capture.

When World War II ended in 1945, the CPM continued to cooperate briefly with the returning British colonial authorities – a political move that has remained controversial even until today. The blame for this "mistaken tactic"was laid on Lai Te, the Party’s General Secretary then, who turned out to be a triple agent working not only for the British but also for the Japanese at the same time. How Lai Te was able to infiltrate all the way to the top leadership of the CPM remains a mystery until today. Little was known about him except that he was originally from Vietnam and had posed himself as a Comintern representative sent from its Hong Kong Office. He was able to gain the trust of the CPM leadership by impressing them with what seemed to be his vast knowledge on Marxism, which was quite rare at that time, considering that most CPM members were much less educated. In 1947, the CPM Central Committee finally discovered his real identity and he was subsequently killed after he had escaped to Thailand. The circumstances surrounding his death and the identity of his killers remain unconfirmed even until today.

Between 1945 – 1948, the CPM engaged in a brief period of open and legal front activities in Malaya, including in Singapore. They were influencing and leading left-wing trade unions, peasant and student movements, some newspapers, as well as other forms of mass organizations. However, the returning British Military Administration after World War II was very ruthless in suppressing the CPM’s activities. By 1948, the British colonial government declared Emergency/Martial Lawin order to eradicate the CPM completely. This period of military and political repression was to last until 1960.

Under the ‘Emergency Rule’, the British stripped the Malayans of all civil liberties, imposed indefinite detention without trial under the Internal Security Act (ISA)on anyone suspected to be a communist or communist sympathizer. Anyone found in possession of subversive materialswere immediately arrested and detained. Summary executions or ‘disappearances’ of activists and suspected CPM members or sympathizers were commonespecially in the areas of military operations by government security forces. These repressive measures finally forced the CPM to once again go underground. From 1948 to 1959, the CPM re-launched its guerrilla war against the British, known also as the period of the Anti-British National Liberation War.

The British colonialists retaliated by employing not only its elite armed forces but also 24 mercenary battalions comprising of Fiji, Africa, Australia and Nepal’s Ghurkha’s soldiers. Furthermore, they also armed the local police force, home guards made up of ordinary folks and several Malay regiments to attack the MNLA. The British employed air strikes, artillery firepower, tanks, armoured military vehicles, and the whole range of modern weaponry against the CPM which by that time, consisted of no more than 8,000 men and women military regulars, supported by about 60,000 members in CPM-led mass organizations.

Not only that, in order to stem out completely the civilian support for the CPM and MNLA, the British authority rounded up mainly the Chinese population and forcefully evacuated them from their homes, in order to put them into concentration campsfar out in the countryside. This is to cut off the support and lifeline of the guerrillas and the underground members, so that they could not easily get their supplies of food, arms and daily necessities from the people. These camps known as ‘the New Villages’, were guarded twenty-four hours a day and surrounded by barbed wires with electricity. Villagers could only use one exit and entrance and they were body-searched each time they left or returned to the camp. Besides their ruthless military methods, the British authority was also guilty of spreading ‘white terror’ or ‘red scare’ by beheading and killing civilians, to ‘weed out’ any possible support for the CPM and its guerrillas’ fighters. As the MNLAbecame more and more isolated and their survival increasingly impossible in the deep tropical jungles, they finally decided to retreat northwards to the no man’s land along the border between Thailand and Malaysia. They set up their base camps in the heart of the impenetrable tropical rainforests and were to remain there for almost half a century until 1989 after the Peace Agreement with the Malaysian government was signed.

It was only in 1955 that for the first time after the party had gone underground; the CPM was able to engage the would-be leaders of Malaya, who were then the Malayan Chief Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman and Singapore’s Chief Governor, David Marshall - in a peace negotiation. However, the peace talk failed because Tunku Adbul Rahman insisted on an unconditional surrender of the CPM, whichthe party could not accept. Consequently, the CPM returned to the jungle and re-launched its guerrilla war. It was only after the Peace Agreement was signed between the CPM and the Malaysian government in 1989 that the guerrillas’ fighters finally laid down their arms and left the jungle.

And this is where the book, "Life As The River Flows" begins...

|

The approach for this series of write-ups will assume that most readers have little intimate knowledge about the history, geography, demography and the socio-cultural atmosphere of Malaysia (which consists of East Malaysia i.e. Sabah and Sarawak and West Malaysia) and Singapore.

Malaysia today has a population of more than twenty million and Singapore, about four million – comprising of mainly Malays, Chinese and Indians, but also a number of other nationalities and ethnic minorities. These are namely, the indigenous communities like the Ibans and Dayaks, descendents of early migrants from as far as the Arabic countries to as near as Indonesia, Eurasians who are of Portuguese or European descent. The last two to three decades of economic affluence in Malaysia and particularly in Singapore, also saw a rapid rise in the number of migrant workers from neighbouring Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand, Sri Lanka, Burma, Bangladesh, India, the Philippines, and increasingly, China nowadays.

Before 1963, Malaya, as then it was called, consisted of eleven states, which included the Peninsula of Malaya and Singapore. However since 1963, the former British territories in Borneo, i.e. Sabah and Sarawak were merged with Malaya to form the Federation of Malaysia. This was an arrangement the British colonialists made to forestall the possibility of Borneo territories falling into the hands of neighbouring Indonesia, which was then led by anti-colonialist and nationalist President Sukarno. He was eventually toppled by Suharto in a military coup with the support of the CIA and the US government. As a result, the people from Sabah and Sarawak were never democratically consulted in the way their independence should have been determined. Therefore, the left wing and progressive movements in Malaysia and Singapore the CPM being only a part of it, never recognised Malaysia as a legitimate country. They also saw the separation of Singapore from the Peninsula of Malaysia to form an independent state on its own, as a ‘historical mistake’ made by the overly ambitious Lee Kuan Yew, the then Prime Minister of Singapore. That is why the CPM continued to refer to Malaya, which includes Singapore, and not Malaysia.

During the British colonial period, most of the Malayslived in the countryside as small farmers and peasants. Traditionally, Malay society tends to be feudalistic in structure and practice, based on a social hierarchy of highly differentiated power relationships with the King/Sultan at the top. Each state in Malaya or Malaysia as it is today, would have its own Sultan. When the British colonised Malaya, they kept the Sultans only as figureheads and deprived them of any real power to rule. To maintain overall control over MaIaya, the British tended to use ‘divide-and-rule’ by playing one Sultan against the other or supporting one brother within a Sultanate over the other in their power struggle.

The Malay society was also traditionally an agrarian society, mainly of landlords and peasants, including many tenant farmers. From the 19th Century onwards, the British brought many Chinese peasants from Mainland China who were keen to escape poverty into Malaya as migrant workers. As a result, the Chinese formed the largest single group of migrant labour in Malaya all throughout the 1950s. At around the same time, the British also brought many poor Indian peasants from the Southern Indian State of Tamil Nadu to Malaya, mainly as indentured labour to work in the British-owned rubber plantations. India was still a colony of the British Empire then.

Hence with these early ‘division of labour’, the three major racial groups in Malaya were kept by and large segregated from one another by the British colonial government’s deliberate divide-and-rule polices. Even though the CPM was able to recruit members from all the three different communities, it was however most successful in attracting and retaining Chinese members. Among many different reasons, the history of its formation probably played a decisive role.

The CPM was founded in April 1930 in a small village near Kuala Pilah in the State of Negri Sembilan (part of the Peninsula Malaysia). Before its establishment, it existed only as a branch of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and was known as the Nanyang Communist Party (i.e. Southseas Communist Party in Mandarin). It consisted almost entirely of Chinese migrant workers from Mainland China, particularly those who were being persecuted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuo Min-Tang or KMT which ruled Taiwan as a single party until 1994) led then by Marshall Chiang Kai-Shek; who later became the first President of Taiwan.

On 30th April 1930, the Shanghai-based Far East Bureau of the Comintern (Communist International) helped organize the first Party Congress of the CPM with Ho Chi Minh attending it as its representative. Ho was then working as a representative of the Comintern. In its early years, the CPM operated as an underground organization. It experienced enormous hardships and was severely hunted down by the British colonial government. The British ferociously arrested, detained and executed party members as well as people who were suspected to be members. Even sympathizers or people who were only remotely associated with such persons were not spared the prison or gallows. Those CPM members who were not sentenced to death were quickly deported to China, even though some of them were actually born in Malaya or have already lived most of their life in Malaya.

However, the CPM were still able to organize workers in the plantations (mainly rubber, oil palm), as well as in tin and coal mines. Workers in the transportation sector of the economy were also recruited and became active members. These establishments were owned mostly by the British and their collaborators. Furthermore, high school students from Chinese schools where the medium of teaching is Mandarin or a specific Chinese dialect also formed a potential pool of recruits for the CPM-led or CPM-influenced student movement and mass organizations. This was in stark contrast to the English-medium schools where the students tended to be much more elitist and pro-British.

When Japan invaded Southeast Asia, the British did not defend Malaya for very longbefore they surrendered both the Peninsula Malaysia and Singapore to the Japanese army. It was an unconditional surrender within 24 hours of Japanese invasion in some parts of Peninsula and in Singapore, despite the confidence of the colonial government of its prowess in its navy and weaponry. The Japanese nevertheless was able to take the colonial army by surprise by literally cycling southwards into Malaya through the border with Thailand in a swift capture, destroy and occupation mission, while the British cannons stood aiming for its enemy at the other end of the Peninsula, towards the Pacific seas.

In fact, the only organized defence then came only from the CPM. And it could only rely on very rudimentary weapons and soldiers with very little training. Therefore, the party had no choice but to enter into a strategic cooperation with the British colonial authorities, so as to gain proper military training and obtain better firearms to defend themselves and the Malayans against Japan. In return, the British released jailed CPM members to form the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), which could then carry out guerrillas operations inside the country just behind the enemy’s line. This tactical coming together between the two enemies lasted from 1941 to 1945 until the end of World War II.

In fact, the MPAJA was even honoured by the Queen of England in 1946 for its contribution to the defeat of Japan with several of its top leaders invited to London to receive their medals. Chin Peng, the Secretary General of the CPM was among one of those honoured. The quote at the beginning of this chapter by Peter Waterman refers precisely to this event. Ironically, soon after this, Chin Peng was named by the British Empire as Enemy Number One and Malaya’s top terrorist on the British most wanted list with a hefty bounty for his capture.

When World War II ended in 1945, the CPM continued to cooperate briefly with the returning British colonial authorities – a political move that has remained controversial even until today. The blame for this "mistaken tactic"was laid on Lai Te, the Party’s General Secretary then, who turned out to be a triple agent working not only for the British but also for the Japanese at the same time. How Lai Te was able to infiltrate all the way to the top leadership of the CPM remains a mystery until today. Little was known about him except that he was originally from Vietnam and had posed himself as a Comintern representative sent from its Hong Kong Office. He was able to gain the trust of the CPM leadership by impressing them with what seemed to be his vast knowledge on Marxism, which was quite rare at that time, considering that most CPM members were much less educated. In 1947, the CPM Central Committee finally discovered his real identity and he was subsequently killed after he had escaped to Thailand. The circumstances surrounding his death and the identity of his killers remain unconfirmed even until today.

Between 1945 – 1948, the CPM engaged in a brief period of open and legal front activities in Malaya, including in Singapore. They were influencing and leading left-wing trade unions, peasant and student movements, some newspapers, as well as other forms of mass organizations. However, the returning British Military Administration after World War II was very ruthless in suppressing the CPM’s activities. By 1948, the British colonial government declared Emergency/Martial Lawin order to eradicate the CPM completely. This period of military and political repression was to last until 1960.

Under the ‘Emergency Rule’, the British stripped the Malayans of all civil liberties, imposed indefinite detention without trial under the Internal Security Act (ISA)on anyone suspected to be a communist or communist sympathizer. Anyone found in possession of subversive materialswere immediately arrested and detained. Summary executions or ‘disappearances’ of activists and suspected CPM members or sympathizers were commonespecially in the areas of military operations by government security forces. These repressive measures finally forced the CPM to once again go underground. From 1948 to 1959, the CPM re-launched its guerrilla war against the British, known also as the period of the Anti-British National Liberation War.

The British colonialists retaliated by employing not only its elite armed forces but also 24 mercenary battalions comprising of Fiji, Africa, Australia and Nepal’s Ghurkha’s soldiers. Furthermore, they also armed the local police force, home guards made up of ordinary folks and several Malay regiments to attack the MNLA. The British employed air strikes, artillery firepower, tanks, armoured military vehicles, and the whole range of modern weaponry against the CPM which by that time, consisted of no more than 8,000 men and women military regulars, supported by about 60,000 members in CPM-led mass organizations.

Not only that, in order to stem out completely the civilian support for the CPM and MNLA, the British authority rounded up mainly the Chinese population and forcefully evacuated them from their homes, in order to put them into concentration campsfar out in the countryside. This is to cut off the support and lifeline of the guerrillas and the underground members, so that they could not easily get their supplies of food, arms and daily necessities from the people. These camps known as ‘the New Villages’, were guarded twenty-four hours a day and surrounded by barbed wires with electricity. Villagers could only use one exit and entrance and they were body-searched each time they left or returned to the camp. Besides their ruthless military methods, the British authority was also guilty of spreading ‘white terror’ or ‘red scare’ by beheading and killing civilians, to ‘weed out’ any possible support for the CPM and its guerrillas’ fighters. As the MNLAbecame more and more isolated and their survival increasingly impossible in the deep tropical jungles, they finally decided to retreat northwards to the no man’s land along the border between Thailand and Malaysia. They set up their base camps in the heart of the impenetrable tropical rainforests and were to remain there for almost half a century until 1989 after the Peace Agreement with the Malaysian government was signed.

It was only in 1955 that for the first time after the party had gone underground; the CPM was able to engage the would-be leaders of Malaya, who were then the Malayan Chief Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman and Singapore’s Chief Governor, David Marshall - in a peace negotiation. However, the peace talk failed because Tunku Adbul Rahman insisted on an unconditional surrender of the CPM, whichthe party could not accept. Consequently, the CPM returned to the jungle and re-launched its guerrilla war. It was only after the Peace Agreement was signed between the CPM and the Malaysian government in 1989 that the guerrillas’ fighters finally laid down their arms and left the jungle.

And this is where the book, "Life As The River Flows" begins...

Real editing time : January 14, 2008

Registration : January 14, 2008

Registration : January 14, 2008

trackback URL http://www.newscham.net/news/trackback.php?board=news_E&nid=45932 [copyinClipboard]