all text articles

Home > list > international

"I hope my mother is proud of me"

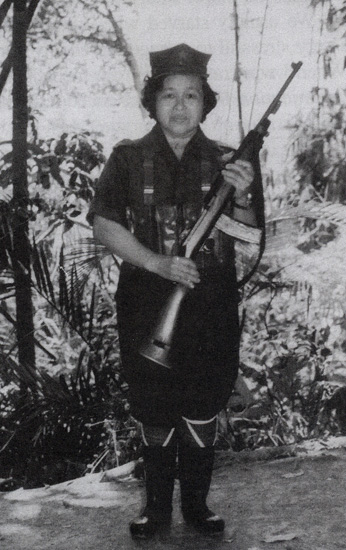

[Life as the River Flows](9)Huang Xue Ying (Born in 1934, Perlis, Malaysia)

Agnes Khoo

|

We accumulated many good and important experiences from our sacrifices and losses. So even though we are not professors and intellectuals, our 40 years of life in the jungle is not a blank piece of paper. Poor people have their virtues, principles and morals. Poor people have backbone....

I value my history very much. I do not want to criticise or negate our past. Even though I am not a hero, I am still proud of our history. I hope that our younger generation find our experiences useful – that they can reflect upon them and value them. Then I will not have wasted 41 years of my life. I feel lucky too, that I am still alive today." These are Xue Ying’s usual anecdotes.

The Japanese Occupation

When the Japanese invaded Malaya, I was in my teens. The Japanese soldiers would urinate everywhere in public. They even bathed naked in public. If a girl passed by, they would call out to her to come to them. They behaved like beasts. At night, they would come knocking at our doors, so girls had to run away to hide in the jungle and swamps. The people feared these soldiers more than the tigers. They raped women and took things from our house. They were more disciplined after the military police came. Soon all schools were teaching in Japanese, they sent teachers from Japan to Malaya. It felt like the whole of Malaya was theirs. I did not go to school because my family was too poor. Then the Japanese left and the British came back. The communists were by this time, organizing people into Youth Groups, Women’s Associations and Veteran Associations.

The Attraction of the Movement

I became actively involved in 1948. The communists organized night schools and outings for us. They read us the Party’s newspapers. I hardly knew a word then. They taught us that women were the most oppressed class, they awakened our consciousness. They told that if we wanted to improve our lives, we had to work hard. Those with money to share their wealth and those without can contribute our labour. I joined the movement as a member of the Civilian Unit in my village. My job was to collect monthly fees from party’s supporters. We also sent food donated by sympathizers to the guerrillas staying nearby.

I joined the guerrillas because I knew they were good people. I had no chance to study and the communists taught me a lot. I felt this was the path I should take to have a decent future. My family was very much against my decision. They nearly skinned me alive when they found out. They tried to deter me with both the ‘carrots and the sticks’. To stop me from going out, they soaked the rice in the water so that I had no food at home or locked me out of the house at night if I returned home too late. They also tried to bribe me with goodies and even offered to send me to school in Penang, another city far away in Malaya. But I persisted even though there is a price to pay for choosing this path. We were pioneers, opening up the way for those after us.

Escape from Home

I asked the party to let me join the guerrillas when I was 14 but they refused because they thought I was too young. They only agreed 2 years later. That day, all my family members were away and I was alone at home, looking after my nephew. I took the chance and ran out of the house immediately. I ran and ran, passing many houses along the way. I was going to my team leader, Ah Fong, who lived at the edge of the jungle. Unfortunately, my mother was already at Ah Fong’s house before me. She persuaded Ah Fong to give me up and accused Ah Fong for influencing me. She said now that I have grown up, I should be staying at home to help out with the family. My mother cried bitterly. But my mind was made up. My sister who was the president of a women’s association under the Party had wanted to join the guerrillas too but my mother managed to persuade her not to go. My brother too had joined the guerrillas before. But he could not stand the hardship and left.

Japanese comrades

I was taught medicine by our Japanese comrade who was also a military doctor in the Japanese army before. In my unit, there were 10 Japanese comrades; one of them was a vet, others were experienced chefs. Some of them were University Professors. These were Japanese who refused to surrender at the end of WWII to the Allied Forces and joined us as guerrillas’ fighters instead. Ah Fu was a firearms specialist and he also knew acupuncture and music. He was very talented and he taught us Japanese songs, dances and judo. Perhaps, our party did not deal with them properly. Some of them walked out on us, others were martyred during fighting with the enemies. Ah Fu was one of those who had tried to escape. Together with four or five other Japanese, they tried to set up another unit by themselves but they failed. They were so hungry they resorted to stealing cassava from the masses and begging for food. This lasted for more than a year before the party found them and brought them back to the camp. They were so thin by then, with long hair and long beard.

The taste of Hunger

|

Our Orang Asli comrades

I was once a section leader to a group of Orang Asli comrades, these were indigenous people who live deep inside the rainforests. They were both men and women, all 17 of them. We escorted them all the way to our campsite and we welcomed them warmly. They could build their own kind of houses at the campsite, made of bamboo and rattan. There would be space below their houses to build a fire, to keep their feet warm at night. They do not use blankets. The Orang Asli should not be looked down upon. They have their wisdom and capability. They told us that the enemy had kidnapped many of their youngsters and took them far away by helicopters for training. They then returned as informants and agents for the government to fight us.

When our Orang Asli comrades were with us, we tried to make them feel at home by building them a stage for their traditional dancing. Their dances have a unique rhythm; they would dance until they entered a trance. They also drank a very strong home-brewed liquor and I used to enjoy myself, drinking and dancing with them. They were good at trapping mice too. They grilled the mice, skinned them and ate them immediately. They offered the heads of the mice to me as a delicacy; it was their way of showing respect. Finally, our Orang Asli members decided to return to their community because they were not used to collective living like us. They needed to be free, to roam around in the jungle and hunt for game. Collective living is like tying up their hands and legs. But we are still grateful to them for having supported us in the past.

Life as a Guerrilla Leader

Becoming a leader in the guerrillas’ army did not depend on one’s education. People were promoted to section leaders, cadres or high-ranking leaders based solely on performances. People were also assessed by their attitudes and way of thinking. One needs to be both virtuous and talented to move up the rank. I was finally promoted to deputy-leader of a sub-unit before we left the mountains. Before this, I was a section assistant, promoted to assistant section leader and then section leader. My main duties were transporting food and sentry duties. I also organized my comrades to clear wild land for planting vegetables.

The 20-month anti-offensive operation

This happened in 1970s. We were at the Command Headquarters of the Third Regiment. A troop was dispatched to escort a unit of 40 to 50 people south into Malaysia. We were to take with us weapons and money, among other things. We also had to escort a team of technicians including the telegram officers southwards. We prepared for these trips for a long time. It took us a full month to go and return. We built bamboo rafts to cross the huge Perak River. We were also carrying a bag full of important letters from the Party. During our journey, our reconnaissance team reported that they had spotted enemy soldiers down the river. They estimated that the distance between us was only about one hour on foot. One of our members overheard that and walked out on us. He surrendered to the enemy. As soon as we discovered that he was missing, we had to retreat. Before long, the enemy bombs started to rain down upon us.

The so-called 20 month-long anti-offensive operation began due to a joint military operation between the Malaysian and Thai governments. So even our Command Headquarters had to move. This was a very big operation which needed several hundred trucks to move many things; food, medicine, even factories. We had to hide those things we could not bring with us. At night we had to cook ‘ba ma’ – a kind of black paste made from the white flower trees, that worked as glue to seal our boxes and containers. It took us months of sleepless nights in order to move out of the place successfully. We were carpet-bombed by our enemy’s planes. Each time the planes came for us, we had to take our rucksacks off and hid quickly behind trees or inside the hollow trunks of huge trees, if we were lucky enough to find these. We tried to follow behind the tail of these planes to avoid their fire. In the 20 months that ensued, the enemy used big bombs, rockets and planes against us. We retreated all the way back to the Hala River, right into the deepest part of the jungle. It took us a long time to get out of the danger completely. We had so little food with us, each person could only eat three spoonfuls of fried noodles a day and we only drank rainwater. We were surrounded then. Those women who were having menstruation really suffered. We were sweaty and we kept urinating all the time. I had to conserve my underwear by wrapping it with plastic sheet. We could not change our clothes or bathe for days. Both sides of my inner thighs became infected because of this. For over a year, we did not taste a cube of sugar. Since I am a coffee addict, I really suffered during this episode of enemy ambush. In the past, no matter how bad things were, we could still have at least one cup of coffee a day. During better times, we could even enjoy green bean soup. But in those hollowing 20 months, we literally had nothing.

Marriage and divorce

Ah Yum, my ex-husband, was a high-ranking officer in the Party. He made some mistakes and as a punishment, he was transferred to our unit. That was how we met, I was only 17 years old then. He was very nice to me and praised me a lot. But we only got married after I turned 25 years old. I thought he would have turned over a new leaf but 7 years after our marriage, he reverted to his old self again. He was flirting and having affairs with other women comrades. I tolerated the situation for 5 years and finally, I told him that my ‘landmine’ would explode if he pushed me too far.

The final break with my husband came when he was discovered to be having an affair with a married comrade. I reported it to the leaders and they were both punished. This marriage really hurt me badly; it was a big blow to me. I am still angry with him. I could have forgiven him then if he was sincere about changing himself. But he was only good at telling ‘long stories’, preaching high morals without practising any of what he said. He was without shame or conscience. I told him how I honestly felt about him in our last meeting, in front of our unit leaders. I told him he was not fit to be our leader. I lectured him for 3 whole hours. After that, there was no way for us to be friends again. Actually, he was the one who asked for the divorce. I could have refused him and the army could also refuse his application. I have never cheated on him. Many women comrades were angry at the way he had treated me. Even though I received many marriage proposals after my divorce, I have resolved to remain single. I could not find any good man. My ideal husband should be someone who care and support me and vice versa. I don’t like men who rely on me for a living or who expects me to take care of his daily lives. I prefer someone who is as independent as I am. In fact, I have managed very well on my own all these years. I have proven that women can live on our own well and happy.

Being a parent

We had a daughter together. She must be about 39 years old now. But we had to give her away as soon as she was born because the jungle was not safe for her. A Thai family adopted her. She grew up like any Thai person and has recently married a Thai Fisherman. I do not mind his nationality; after all, it’s her marriage, not mine. As parents, we should not interfere in our children’s choice of partners...if they want to marry someone outside our community or race, we should let them decide for themselves. No one can make such an important decision for them. I do not dream of her marrying a rich capitalist because a rich man would take many wives. I did not attend her wedding but she sent me their pictures. My daughter and my son-in-law live an honest, hardworking and simple life. No need to dream about becoming a millionaire. There are so many poor people in this world; they live on anyway, as best as they can. Too much money can also be a bad thing. I feel responsible for bringing my daughter to this world even though I did not fulfil my responsibility of bringing her up. She will inherit my rubber holding and fruit garden when I die. She is the only one in the world for me.

After we left the mountains in 1989, we looked all over the place for her. My comrades helped me to locate her in Bangkok. I was very touched when she addressed me as ‘Mother’ at our first meeting. She would buy me fruits whenever I visited her family. When her foster family was told that I was her biological mother, her foster mother kept crying because she thought I would take my daughter back. But I assured her that this was not my intention and that I only wanted to thank them for taking care of my child.

Going Home

Our status in Thailand is that of an Overseas Chinese. I would not compromise my political position and revolutionary history just to return to Malaysia. I have tried to apply for a visitor’s visa for Malaysia but the government refused me. I only wanted to pray at my mother’s grave in my hometown for her forgiveness on the Chinese All Souls’ Day. I think I have shown my love for my mother by joining the revolutionary struggle because we were fighting for an independent Malaya, free from the colonialism and imperialism of the British and the Japanese. My mother is a Malayan citizen, so I was also fighting for her freedom. This is my contribution to her; I hope she is proud of me.

Real editing time : September 9, 2008

Registration : September 9, 2008

Registration : September 9, 2008

trackback URL http://www.newscham.net/news/trackback.php?board=news_E&nid=49485 [copyinClipboard]